Microblog

A Pathogen’s Passport: Implications of an Increasingly Connected World

Throughout history, human travel has been heavily implicated in the spread of infectious disease. Whether it be British troops whose movements spread cholera out of India in the 1800s, or Europeans whose arrival brought smallpox to the Americas in the 15th century, many of history’s most deadly pandemics can be traced to human movement (Tatem et al., 2006). Though the spread of pathogenic microbes via human travel is not a new phenomenon, the unprecedented increase in global air travel has brought about a modern era for the spread of infectious disease. Within hours, an infected human can travel to another hemisphere, unknowingly spreading their disease across distant borders. This has become abundantly clear during the current COVID-19 pandemic, where it took less than two weeks from the virus’s initial identification in China for a case to be confirmed thousands of kilometres away in Thailand (World Health Organization, 2020).

Throughout history, human travel has been heavily implicated in the spread of infectious disease. Whether it be British troops whose movements spread cholera out of India in the 1800s, or Europeans whose arrival brought smallpox to the Americas in the 15th century, many of history’s most deadly pandemics can be traced to human movement (Tatem et al., 2006). Though the spread of pathogenic microbes via human travel is not a new phenomenon, the unprecedented increase in global air travel has brought about a modern era for the spread of infectious disease. Within hours, an infected human can travel to another hemisphere, unknowingly spreading their disease across distant borders. This has become abundantly clear during the current COVID-19 pandemic, where it took less than two weeks from the virus’s initial identification in China for a case to be confirmed thousands of kilometres away in Thailand (World Health Organization, 2020).

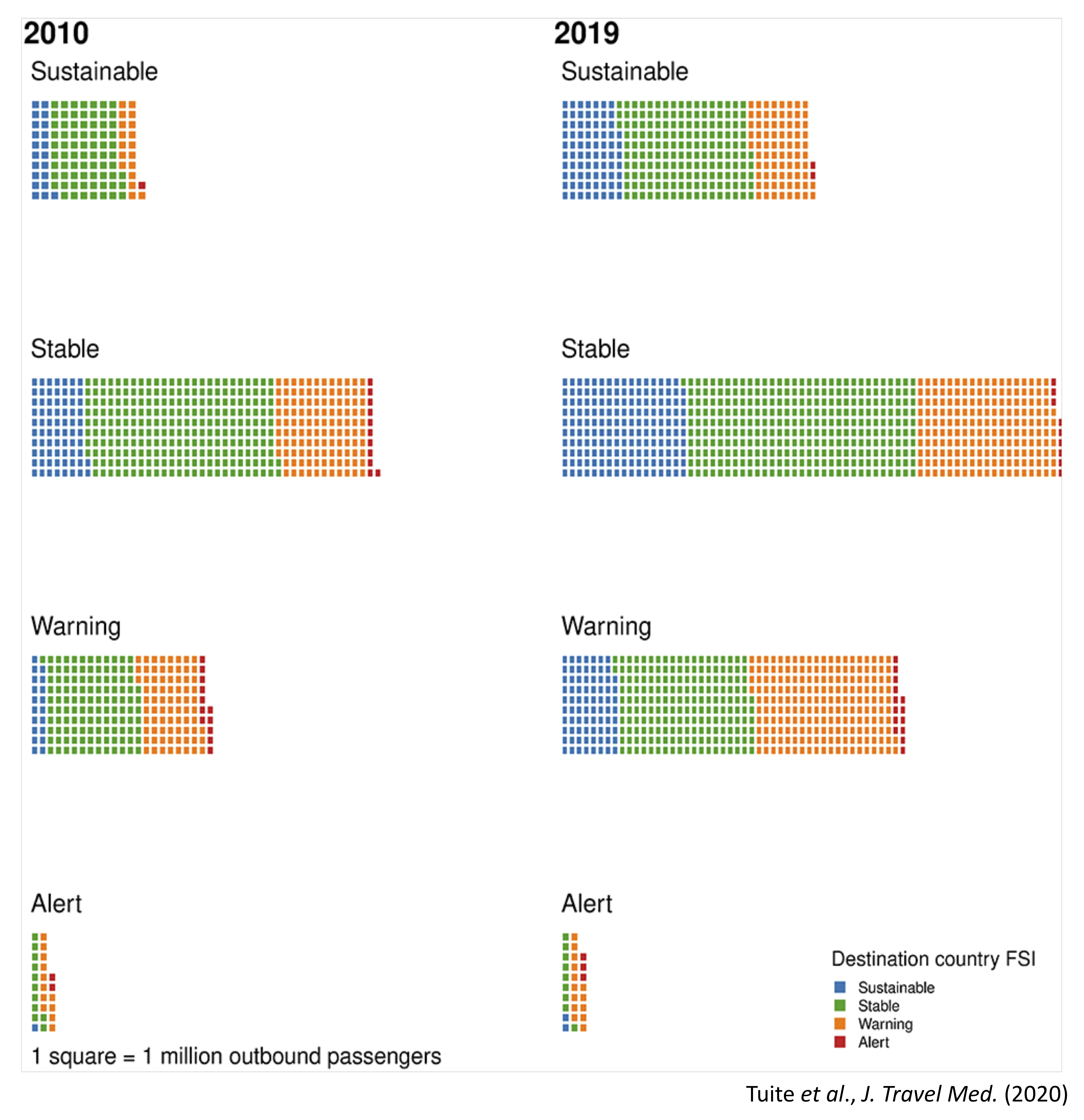

The relative risk associated with the introduction and spread of infectious disease is complex and cannot be explained alone by the increased volume of global travel to a particular region. One key consideration is the disparity among countries in their ability to detect and respond to an infectious outbreak. As such, increased travel to and from more vulnerable countries may increase the likelihood and speed of global transmission (Tuite et al., 2020). A fascinating new paper by Tuite and colleagues published in the Journal of Travel Medicine delves into this topic by analyzing trends in international air travel over the past decade between countries with varying resilience to infectious disease threats.

To measure how well a country responds to the threat of infectious disease, the authors utilized the Fragile States Index (FSI), which scores 178 countries based on 12 indicators designed to assess their vulnerability to collapse or conflict (The Fund for Peace, 2020). These countries have been assigned an FSI annually since 2005, and can be ranked into one of four categories: Sustainable, Stable, Warning or Alert (The Fund for Peace, 2020). Of the 46 countries that had one or more disease outbreak(s) in 2016, 70% were in the Warning or Alert category, suggesting the FSI to be a useful measure of a country’s capacity to respond to infectious disease threats (World Health Organization, 2016; Tuite et al., 2020). For each of the 178 countries analyzed, the authors also obtained the total number of annual inbound and outbound international passengers from 2010-2019 from the International Air Transport Association.

Over this past decade, the authors observed a dramatic 80% increase in the total number of international passengers, surpassing 1.5 billion outbound individuals in 2019 (Tuite et al., 2020). Countries from all FSI categories contributed to this increase, although the largest number of passengers travelled from countries designated as Stable. There was a significant negative correlation between a country’s FSI value and its travel volume, with every point increasing a country’s fragility score being associated with a 2.5% reduction in passengers. This was taken as a positive sign, as it suggests the largest volume of passengers travel from countries with good capacity to deal with infectious disease threats. However, more concerning trends were found as well. For example, reciprocal travel between Warning countries has increased over time which could potentially result in greater spread across regions with suboptimal infectious disease control infrastructure. In addition, the number of international visitors to Alert and Warning countries has increased over time which may increase the export of infectious disease from these countries when travellers leave.

As the authors point out, the current pandemic highlights that even well-prepared Stable countries may not sufficiently implement proper detection and control measures. However, understanding international air travel trends remains crucial for predicting disease spread and identifying countries with the greatest vulnerability to an outbreak (Bogoch et al., 2020; De Salazar et al., 2020). Increased global mobility has undoubtedly produced tremendous benefits to humanity but being couriers for pathogenic microbes means that improving global surveillance, communication, and control measures must be a priority.

Primary research article:

Tuite, A.R., Bhatia, D., Moineddin, R., Bogoch, I.I., Watts, A.G., Khan, K., 2020. Global trends in air travel: implications for connectivity and resilience to infectious disease threats. J Travel Med. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taaa070

Other references:

Bogoch, I.I., Watts, A., Thomas-Bachli, A., Huber, C., Kraemer, M.U.G., Khan, K., 2020. Pneumonia of unknown aetiology in Wuhan, China: potential for international spread via commercial air travel. J Travel Med 27. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taaa008

De Salazar, P.M., Niehus, R., Taylor, A., Buckee, C.O., Lipsitch, M., 2020. Identifying Locations with Possible Undetected Imported Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Cases by Using Importation Predictions. Emerging Infect. Dis. 26. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2607.200250

Tatem, A.J., Rogers, D.J., Hay, S.I., 2006. Global transport networks and infectious disease spread. Adv. Parasitol. 62, 293–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-308X(05)62009-X

World Health Organization. 2016. Disease outbreak news: Archives for 2016.

https://www.who.int/csr/don/archive/year/2016/en/ (accessed 6.5.20).

World Health Organization. 2020. WHO Timeline – COVID-19. https://www.who.int/news- room/detail/27-04-2020-who-timeline—covid-19 (accessed 6.5.20).

The Fund for Peace. n.d. Fragile States Index. https://fragilestatesindex.org/methodology/

(accessed 6.5.20)

Cowen LAb

Posted on : 17/06/2020 9:00 AM

Liked this post?

Click the social media icons on the left to share!

Have anything to say? Comment below!